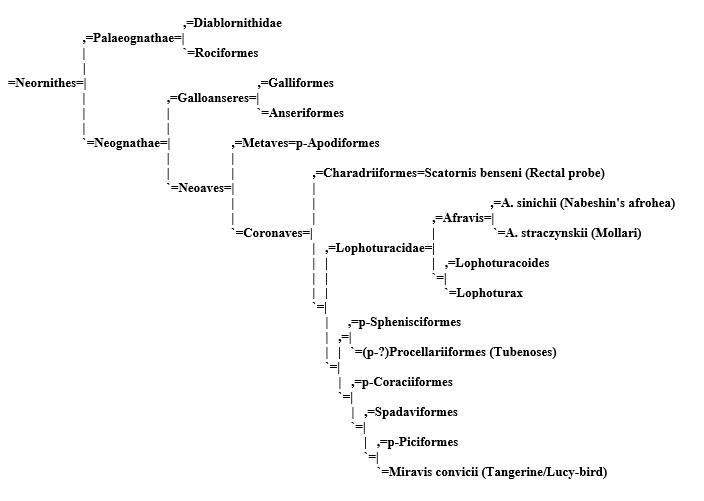

At the end of the Cretaceous, as Spec and Home-Earth began to diverge, birds had already been evolving for at least 80 million years and had diversified widly. In fact, diversity of bird types (though not actual species count) was far higher in the late Mesozoic than it is today in our timeline, and it has seemingly stayed so in Spec. In Spec, the so-called opposite-birds (Enantiornithes) make up the biggest part of bird diversity. However, Neornithes, the only bird group that has survived on Home-Earth, already existed in the Late Cretaceous, and has survived and diversified in Spec. Most waterbirds as well as most of the less conspicuous groups of landbirds are neorniths. Thus, in many respects, the bird fauna of Spec is very similar to that of Home-Earth. There is, however, a number of differences.

PALAEOGNATHAE

In Home-Earth, this group, whose ancestry reaches far back into the Late Cretaceous, includes the chicken-like tinamous of South America and the flightless ratites of several continents. In Spec, few palaeognaths are flightless, and most are carnivorous. Probably this is because the niches occupied by the ratites of our timeline are occupied in Spec by animals such as the nandrakes, the nostrich, the gigaducks (see below) and certain alvies like the Papuan muppet.

DIABLORNITHIDAE (Gobblers) The flightless top predators of Aotearoa

ROCIFORMES (Rocs) Flying scavengers and giant carnivores of the Old World, especially Madagascar

NEOGNATHAE

GALLIFORMES (Henchicks and butters) An old group of widespread ground-dwellers (under creation!)

ANSERIFORMES (Ducks, gigaducks, etc.) An equally ancient group of waterbirds and terrestrial herbivores

p-APODIFORMES (Swoops, minnies, and hummingbirds) The most stunning fliers among Neornithes

CHARADRIIFORMES (Plovers and lots more)

Relatives of plovers, thick-knees, stilts and oystercatchers are seemingly present in the fossil record of the end of the Cretaceous, and have changed little from their long-legged ancestors.

The rectal probe (Scatornis benseni) is a highly specialized hunter of rectal endoparasites and other animals found in the colon of the aquatitan.

See: The Rectal Probe

LOPHOTURACIDAE (Afroheas)

«…something like a turaco […] [Musophagidae], or an aberrant coraciiform? I’ll give these odd birds their own group, Lophoturacidae. Afravis for these two species, and I’ll see about the others, right after I get a good look at those spiny trees.»

– Journal entry recovered from the lost Deep Africa expedition

The recently discovered lophoturacids form a small radiation of basal neornithine landbirds that is, unlike their widespread and omnivorous cousins, restricted in both diet and range. Lophoturacidae is restricted to equatorial Africa, and most common in the Congo Basin, where the specimens pictured below were found. Afroheas range in length from 45 to 70 cm.

Afroheas are adequate, though not expert flyers, but they are very agile on their feet and happily run around in the vegetation. They are noisy and sociable birds, normally found in small flocks. Primarily herbivores, afroheas feed on fruits and seeds, though they will take insects and other invertebrates when the opportunity offers itself. Nests are made of twigs and placed low in the vegetation. The young are born altricial, naked and helpless, and feed on regurgitated fruit and insects for about 4 weeks, by which time they are able to fly and forage for themselves. The parent birds have the curious habit of violently kicking snakes that attempt to steal eggs or chicks.

Courtship generally involves fluttering the wings to display the bright colours, raising and lowering the crest and flicking the tail, followed by the male bringing a food offering to the female. Interestingly, the colours with which the males display are unique to this group. In Lophoturacoides and Afravis, the secondaries (smaller wing feathers) have a red colour from the pigment called lophoturacin, while some species of Lophoturax have a unique green pigment called lophoturacocyanin. The exact reason for the lophoturacids’ independent evolution of these pigments has yet to be determined.

Nabeshin’s afroheas are the largest and one of the most dazzling species of afroheas. These unfortunately reclusive birds can only rarely be spotted in the dense canopy of the Congo rainforest. Their call, however (often transliterated as ‘zalinga-zalinga’), can often be heard near dusk, as the birds call to their mates.

Smaller than Nabeshin’s afrohea, and armed with a robust, seed-crushing bill, the mollari is primarily a fruit- and nut-eater. Its beak has once caused the lophoturacids to be allied with parrots in the eyes of some researchers – until Spec’s «parrots» turned to be something else entirely.

While fully as colourful as its canopy-dwelling cousin, mollaries are nearly mute, and so far less noticeable in the dark Congo rainforest.

p-SPHENISCIFORMES (Penguins, penguins of death, aviserpents, and teals) The southern equivalents of seaguins and selkies

(p-?)PROCELLARIIFORMES (Tubenoses) Like in Home-Earth

Petrels, diving-petrels, storm-petrels and albatrosses exist in both timelines. It is still an open question whether this is due to convergence or proves that the fragmentary Cretaceous remains assigned to Procellariiformes in fact belong there; but, either way, to describe the tubenose species of Spec would for the most part be a useless exercise in repetition. The same holds for several other bird clades that we haven’t bothered to mention in this book.

p-CORACIIFORMES (Nearcrows and kingfishers) The good, the bad and the ugly

SPADAVIFORMES (Jaubs and pickpeckers) Most typical birds that aren’t tweety-birds belong here, as do several more spectacular examples

p-PICIFORMES (Muzzle-toucans, fairy-barbets, and waterfall-barbets) Brightly coloured tropical birds

Miravis convicii (Tangerine/lucy-bird)

The misty isles of Aotearoa host a miraculous diversity of birds, such as the ferocious gobblers and the gargantuan gigaducks, but one species, ridiculously tiny next to its colossal neighbors, is perhaps the strangest of all – or the most familiar.

Endemic to Aotearoa, the tangerine (Miravis convicii) is the closest Spec has come to producing a true songbird (Passeriformes). This small bird possesses normal anisodactyl feet, with toes II, III, and IV directed forward, while toe I is fully reversed and capable of independent movement. Tangerine plantar tendons and forearm muscles are also passerine, although the tangerine lacks the diagnostic aegithognath palate. Its stapes (middle ear bone) closely resembles those of the Home-Earth riflemen or New Zealand wrens (Acanthisittidae). In fact, the tangerine resembles riflemen a great deal in outward appearance, although some of this resemblance is surely convergent.

More detailed analyses of this bird, including examination of their syringeal anatomy and their DNA, have yet to be conducted, but the tangerine seems to represent a very basal branch of the clade that has, on Home-Earth, led to the passerines, familiar to all Home-Earth natives, though completely inexistent in Spec.

Tangerines, named in accordance with the ancient Aotearoan tradition of naming small birds after fruit, are rather unassuming birds, locally common in pockets all over both North and South Island, with a number of regional varieties. These little birds eat insects, which they catch in bark, leaf litter, or (occasionally) on the wing. Tangerines are sexually dichromatic, the males sporting brilliant orange-and-red plumage and the females being a rather nondescript brown. Eggs are laid in early September and the helpless young are fed by their parents until old enough to fly (roughly a month after hatching). Tangerine vocalization is a muted «loo-tsiiii«, probably responsible for their alternate name, «Lucy-birds».

Daniel Bensen, João Boto and David Marjanović